Skins - Gavin Watson (Livro)

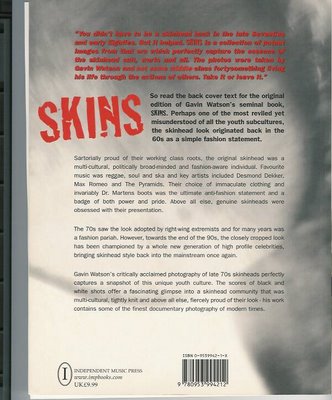

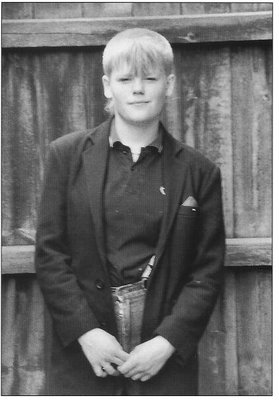

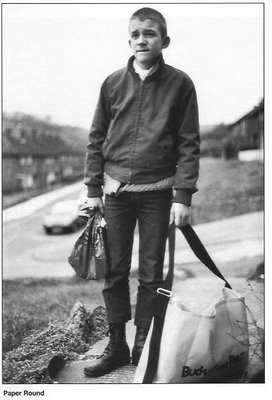

Esta segunda imagem é a capa da reedição do livro. penso que qualquer uma delas é um espectáculo. A grande mais valia deste livro é a naturalidade com que estes jovens skins aparecem nas fotos. Foram retratos tiradas espontaneamente por um jovem skinhead aos seus companheiros e companheiras de rua. A vida do bairro, a escola, o trabalho, os tempos livres, todas estas situações são retratadas no livro com a maior naturalidade. Em seguida fica a contracapa da segunda edição do livro.

Para completar o máximo possível esta notícia vou colocar aqui um video onde Gavin Watson fala sobre o livro. Coloco ainda uma entrevista, feita em 2003, a Gavin Watson, para o site 'Open Democracy'. A entrevista, em inglês, vai acompanhada de algumas das fotos que poderás encontrar no livro.

Skinning up

Hair as political protest, or global fashion? Photographer and one-time Skinhead, Gavin Watson tells it how it is - in pictures and words.

Anamik Saha: What are the roots of the Skinhead movement?

Gavin Watson: It was a natural transition from the 1960s Mod movement. The Mods were hijacked by the middle classes, and the Beatniks - before they turned into hippies. So the younger Mods hardened their image, wore stuff the middle classes wouldn’t - donkey jackets and boots. They cut their hair shorter than anyone else, and after a football riot they were dubbed ‘Skinheads’ by the tabloid the Sun newspaper. Originally they’d just called themselves ‘hard Mods’.

AS : What were the politics behind shaving your head?

GW: It was in total contrast to the hippy movement. It was a working class rebellion. Of course a shaved head has come to mean something different over the years, and changes according to context – from Buddhist monks, the gay scene to David Beckham.

AS : In your book, Skins, you say it was ‘one of the most reviled yet misunderstood of all the youth subcultures’. But wasn’t the politics all about confrontation, challenging the status quo?

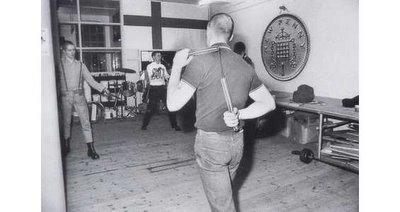

GW: Definitely. It was a punk attitude, a stand-off. ‘We’ve got our tribe, this is our area. This is who we are. This is our gang.’ It’s the same with all gang culture. Ultimately it was a fashion, but it was quite a distinct one.

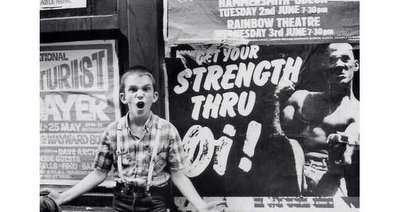

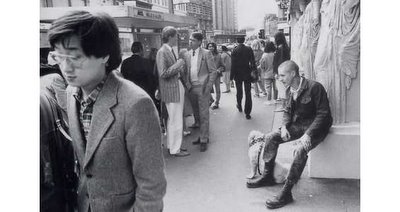

AS : I’ve always associated Skinhead culture with the socio-economic and political climate of the time, growing up in the 1970s and 1980s. But your photographs convey a sense of innocence and youthfulness, an interesting challenge to the pervading stereotypes.

GW: I was around fourteen when I took these photographs. I wasn’t a full-grown man hanging out with kids. They’re pictures of my brother, friends, council estate, the school I went to. It was what I saw through my own eyes. I was into Madness and the Specials. I was young and innocent, a teenager growing up.

The people I photographed are just kids – maybe disturbed or violent, but still little teenage kids, acting hard. It’s the reality of growing up on a council estate, in government housing, same as anywhere around the world. It’s not what journalists are writing about, not what you see in the newspapers. It’s reality. Now the kids are into rap and So Solid Crew. The music is different. But nothing’s changed.

AS : You said that Skinheads were never a threat to world peace…

GW: Right. It was just another subculture. We weren’t beamed in from Planet Nazi. But even intelligent people, who wouldn’t believe a word of what’s going on politically say with Bush, still they have incredible stereotypes about working class culture. ‘All Skinheads are Nazis.’ Actually, it comes out of Jamaican culture.

AS : Yes, the interaction between white and black youth in the reggae culture of the late 1960s. But it’s a popular conception that skinheads, racism and neo-nazism go together. So what did being a Skinhead mean to you?

AS : Yes, the interaction between white and black youth in the reggae culture of the late 1960s. But it’s a popular conception that skinheads, racism and neo-nazism go together. So what did being a Skinhead mean to you?

GW: Originally, it meant a great laugh. Discovering Madness. Having my hair cut - and the things all teenagers go through the world over: finding a sense of belonging and working towards autonomy. That’s how it started for me. For others it might’ve been Led Zeppelin, whatever. But it got me into my teenage years. I felt protected. I grew up in a very, very violent place. For many of us, being a Skinhead was about protection. We had our mates. We’d watch each other’s backs.

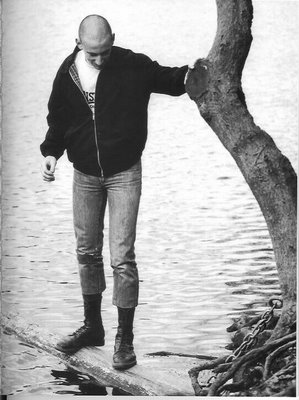

AS : And the symbolism in shaving your head?

GW: It was a personal commitment. You couldn’t just be a weekend punk. You had to be a Skinhead. You had to go to work as a Skinhead. You had to start your life as a skinhead. When you went to a job interview, you had to fight against what people thought of you. It was a matter of pride. A statement: ‘I’ve chosen this, it means a hell of a lot to me.’ In a way, just by shaving your head then, you became a Skinhead. You committed yourself at a time when you were vilified. Now, after David Beckham, everyone’s done it. But back in the late 1970s and 1980s, there was a lot of violence. Being a Skinhead was your way of saying, ‘This is my tribe. This is where I come from.’

AS : Have Skinheads been co-opted by the mainstream?

GW: It’s still vilified, but then every fashion house has my book. Paul Smith used my photographs to design part of a fashion collection. Clark’s shoes used the images for inspiration. Skinheads influenced modern male culture, especially the late 1990s ‘lad culture’. All the late-20s guys who used to be terrified of Skinheads could buy their Crombie coat, shave their heads and act hard, Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels-style. At the time, they’d never have had a Skinhead. But suddenly it was safe. Now it’s acceptable to look like a total Skinhead, without even thinking you look like one. But I stopped being one a long time ago.

AS : I’m Asian, 25 years old, and I grew up in the late 1980s. Obviously Skinheadism was something I felt quite intimidated by…

GW: I’m not surprised! The Indians and Asians were the new immigrants and there was a lot of fear. They took the brunt of it, the same way the Somalis do now. I heard about a middle-aged Sikh recently who beat up a Somali, saying, ‘You don’t belong here, you don’t come from round here, get back to your own country.’ It’s a horrible story, but my point is this: we’re all bastards, whatever colour we are. Good people, bad people. It’s not a colour or genes thing, not natural but societal. We’re all bastards, mixed in together.

I remember an exhibition I had where four civil servants came every night, utterly fascinated by Skinhead culture. One of them, an Asian, got interested in Skinheads after he was beaten up on a bus going to Brixton. He knew more about Skinheads than anyone. What does that make him? They were Skinhead train-spotters. It was great. I had working-class people from the West Indies, Asia, all over the place, saying the Skinhead culture had influenced them. It’s just what happens when you live in a tight community, however widely that spreads – you might go down the pub looking like a Nazi Skinhead but you’ll be swapping teabags the next day. That’s the reality.

AS : About five years ago, the second-generation Asian thing became a fashion. Quite funny for me, actually, suddenly to ‘become a fashion’, and I remember a photoshoot of Asian youths dressed up as Skinheads…

AS : About five years ago, the second-generation Asian thing became a fashion. Quite funny for me, actually, suddenly to ‘become a fashion’, and I remember a photoshoot of Asian youths dressed up as Skinheads…

GW: Exactly. It’s all pretty mixed up now. But when I started taking photographs it was against a society that was training you to be an exhaust-fitter or table-leg maker. So I was a Skinhead for ten years. I was a nasty bastard. Six of my mates died. I’ve been stabbed, put in prison.

I think that that’s why the photographs look so innocent. There was so much nastiness around me, I didn’t want to photograph it. If I’d come in as an outsider, I’d have been waiting for the shit to happen. But I was actually living the nasty bits – being poor and working class. I didn’t want to photograph them as well. I just wanted to photograph the good times we were having.

Entrevista realizada por Anamik Saha

Entrevista realizada por Anamik Saha

Fonte: Skinhead Attitude Film / Gavin Watson Book / Gavin Watson Myspace / Open Democracy.

Etiquetas: Entrevista, fotos, Gavin Watson, Livro, Skinhead, Video

0 Comentários:

Enviar um comentário

Subscrever Enviar feedback [Atom]

<< Página inicial